We consider constrained optimization problems of the kind:

where the feasibility region is a polytope, i.e.,

is the set of

such that:

where are real matrices of size

and

, respectively, and

are column vectors. Equivalently, we can rewrite (1) as:

where are the

-th row of

and

, respectively, and

denotes the scalar product.

In this post we will study necessary conditions that function must satisfy at any optimal point

. These are the so-called Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions [1,2], which generalize the classic Lagrangian conditions that are valid under equality constraints only.

1. Basic principle and three open questions

In simple words, KKT conditions state that in a neighborhood of any optimal within the feasible region, the function

must not increase. This requirement is intuitive but leaves us with some open questions like:

- What a (feasible) neighborhood looks like?

- How to know whether

does not increase within the neighborhood?

- How to restate the optimality condition in a form that is actually computable, rather than merely as an abstract definition?

Next we will answer all three questions using geometric insights. Finally, we will also provide an example where KKT conditions actually help us solve the optimization problem.

2. Non-increasing property

Let us place ourselves at the optimum . We look towards all directions emanating from

and we select only those that, if followed even for a tiny bit, allow ourselves to stay within the feasible region. We denote such feasible directions as

and will characterize them in the next section.

Along the feasible direction , function

must not increase, at least locally. In other words, its directional derivative must be null or negative. We recall that such derivative equals the scalar product between the gradient

and

. Thus, the optimality condition can be written as:

Condition (3) is a valid necessary optimality condition, although still quite primitive, since is not defined (yet). However, an important—although not surprising—conclusion stems from it. If

lies in the interior of the feasibility region

, then we can safely travel along any direction without falling outside

. Then,

coincides with the whole set

, hence the gradient must be necessarily null for (3) to hold:

which is the classic first-order optimality condition for unconstrained optimization.

3. Feasible directions

We next refine the optimality condition (3) by characterizing the set of feasible directions , being the directions along which we can depart from

while staying within the feasibility region, even for a small distance.

As it turns out, can be simply defined as the set of vectors

translating

to any other feasible point

:

This stems from the convexity property of the feasibility region : if

is feasible, then any point between

and

is feasible. The same does not hold if

were not convex, as illustrated below.

We can now make the optimality condition (3) more explicit by rewriting it as:

Although we’ve made headway, there is still something unsatisfying about condition (5): validating the relationship across all feasible points feels like too daunting of a task. We will take care of this in the next section.

4. KKT conditions via normal cones

Condition (5) states that, in order for to be optimal, the gradient

must be anti-aligned with all feasible directions departing from

, since its scalar product with each of them is non-positive. More formally, we say that

belongs to the normal cone of

at

, referred to as

:

In the hope of further refining condition (5), we are then interested in characterizing in explicit form.

We build up to its general definition via examples of increasing complexity.

(Temporarily) discard equality constraints . In the next few examples we will then consider only constraints of the kind

. We will later realize that this simplification is actually without loss of generality.

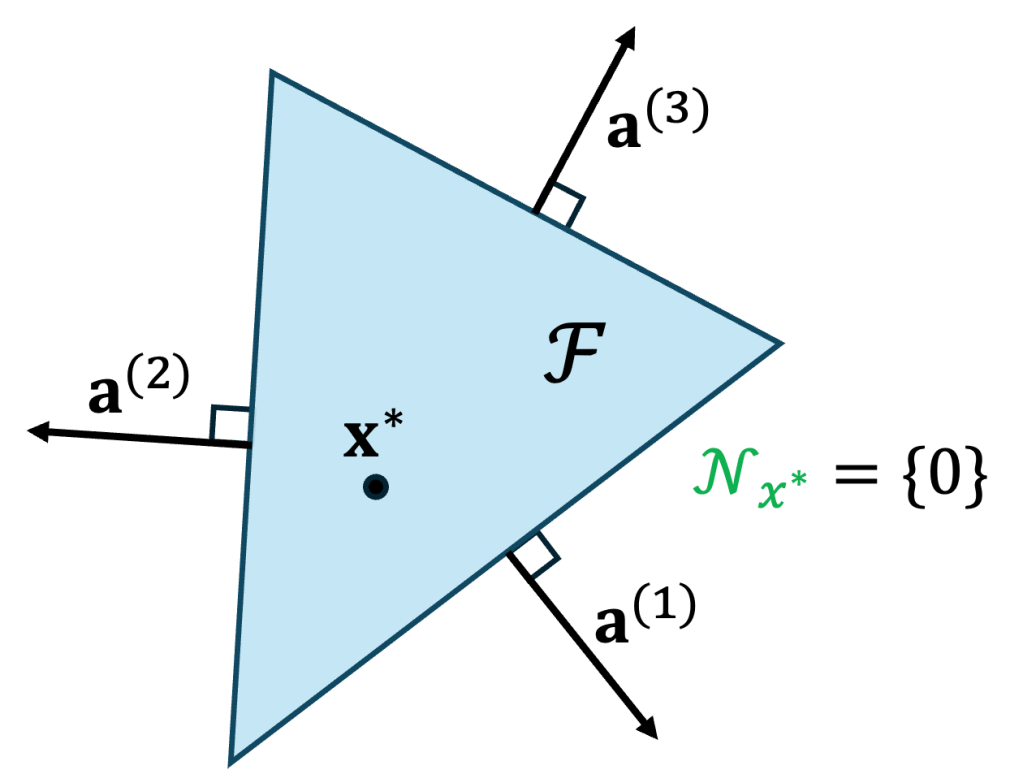

The optimum is inside . If the

is in the interior of

then the normal cone

, as we already discussed:

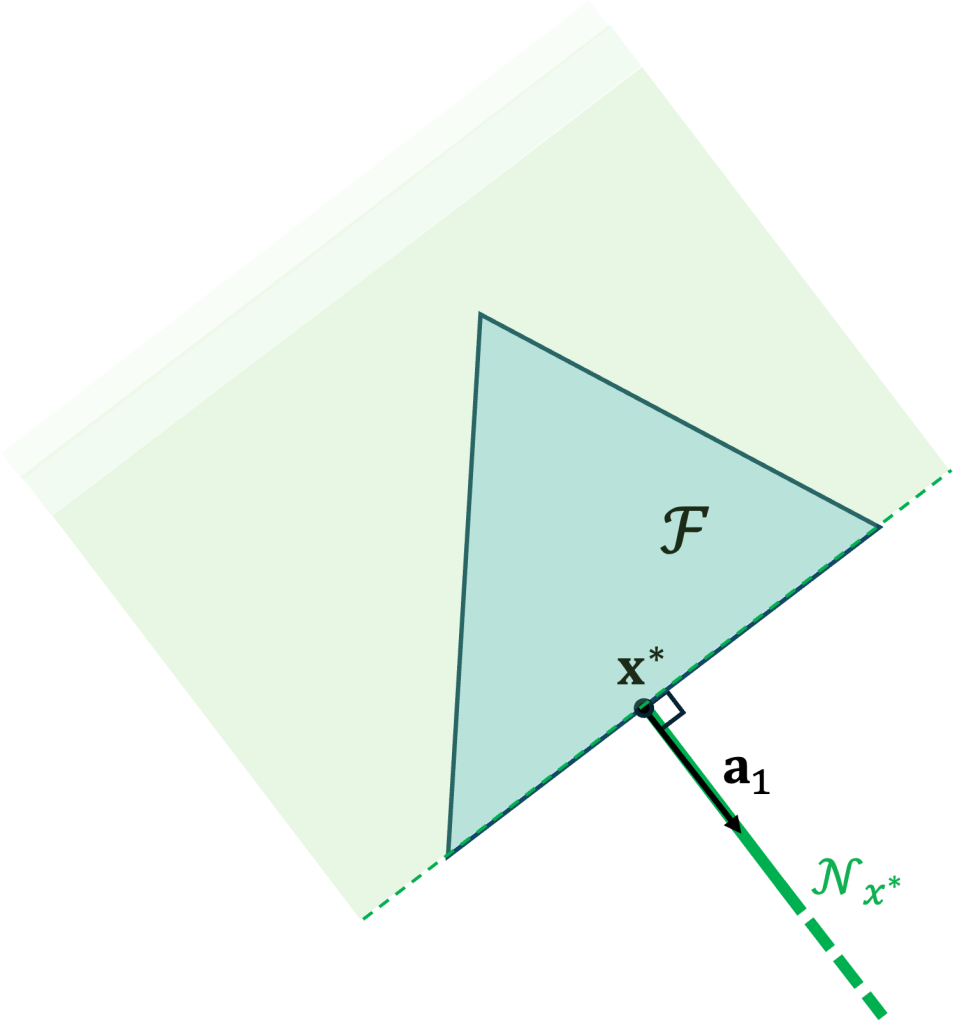

One constraint is tight. Next, we suppose that satisfies exactly one constraint, say the first one, with equality, while the remaining are satisfied with strict inequality. In this case,

lies on an edge of

and the normal cone

coincides with the half line spanning from

:

Observe that the green shaded region denotes the set of vectors that are anti-aligned with , i.e., their scalar product is non-positive. Note that it must contain the whole feasibility set

for

to belong to

.

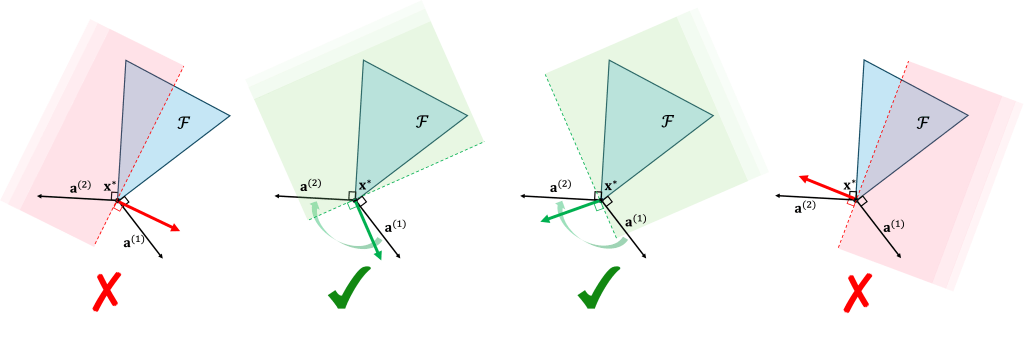

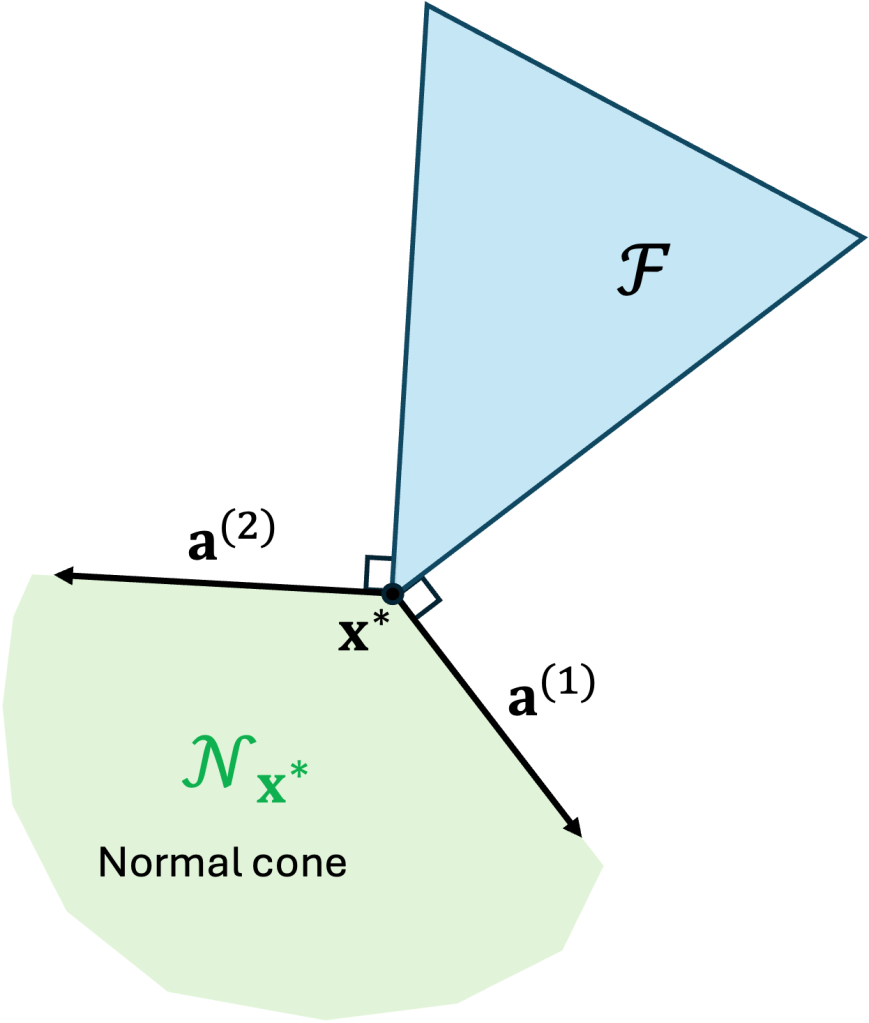

Two constraints are tight. When two constraints are tight—say the first two—instead of just one, the feasibility region shrinks. Hence, we expect that i) the normal cone

enlarges and ii)

still belong to

. Pushing the reasoning further, the visual argument below should convince us that iii)

coincides with all vectors lying in between

and

:

More formally, is the cone spanned by

and

:

where are the so-called Lagrangian multipliers.

Multiple constraints are tight. The same intuitions we just gained with two tight constraints also apply when dealing with multiple tight constraints. To give a final polish to our expression of and make explicit that only the

‘s associated with the tight constraints contribute to forming the normal cone, we can write

where (9) is the complementary slackness condition, claiming that

- if the

-th constraint is loose, i.e.,

, then

, thus

does not contribute to

;

- if the

-th constraint is tight, i.e.,

, then

, thus

can intervene in forming

.

Bringing back equality constraint. We now what we have learnt so far to the initial case with inequality constraints and equality constraints

.

Let us start simple: in the presence of just one equality constraint , the normal cone at

is the whole line perpendicular to

, hence parallel to

, passing through

:

Observe that unlike the inequality case, where multipliers are nonegative, the normal cone is formed by scaling by a multiplier that can be either positive or negative.

To make this statement more formal, we first rewrite every equality constraint as two inequalities:

Then, we assign nonnegative Lagrangian multipliers to the two previous inequalities, for all

, and integrate those in our previous definition of normal cone in (8) to obtain:

It is convenient to assign just one multiplier to the

-th equality constraint; note that

can be either positive or negative, as previously predicted!

We also observe that the complementary slackness condition (9) still holds the same, since equality constraitns are tight by definition.

Putting all together: KKT conditions. After quite some work, we are finally ready to provide the polished version of KKT optimality conditions.

If is an optimal solution to the optimization problem

, then there must exist

such that:

5. A formal proof

For those who want to go deeper, below we prove that the normal cone at point coincides with the cone spanned by the

‘s corresponding to the constraints which are tight at

, as claimed by expressions (8)–(9).

Theorem 1 Let

be the feasibility region with inequalities only and call

the set of constraints being tight at point

. Define

the cone spanned by

‘s corresponding to the tight constraints. Then,

coincides with the normal cone

.

Proof: We first prove that . Given

, we have that for any

:

where the equality in (12) comes from the definition of and the inequality stems from the feasibility of

and the positivity of

‘s. Hence,

and

.

Next, we prove that . By contradiction, suppose that there exists a point

that does not belong to

. Then, we want to prove that

either, i.e.,

for some

. Then, we aim at finding such

.

By the hyperplane separation theorem, there exists a vector such that:

We try with , with

. We first want to show that, for

small enough,

is feasible, i.e.,

We distinguish two cases:

- Case

. Here,

, hence it suffices to choose

smaller than the first value that would violate a constraint, i.e.,

- Case

. Here,

, so it must hold that

for

to be feasible. In that case,

can take on any (positive) value. To prove it we first recall that, by (13),

for all

. Since

, then

Hencefor some

for all

. Since

for any

and with

, then

, or equivalently:

By letting, we obtain

, as wished!

Hence, we showed that, for small enough,

is feasible. Finally, we show that by absurd,

, since

. This stems directly from expression (15):

Thus, and the thesis is proved.

6. Can KKT help us solve the optimization problem?

The answer is yes, although often not in a direct way. Instead, the KKT conditions give us clues about what the optimal solution may look like, and a bit of creativity is required to complete the process. An insightful example is the following:

that often arises in wireless signal processing in the context of power allocation, where and

stand for the transmission power and the noise power on channel

, respectively. Here,

,

is a vector of zeros except for its

-th component being -1 and

. According to the KKT conditions, if

is optimal then there exist

for which:

Then, . However, we know that if

, then

. Moreover,

. Thus, we can rewrite:

where we highlighted the fact that still depends on

, which is unknown. The good value of

, that we call

, fulfills the equality constraint, i.e.,

Since is a decreasing function of

, one can use the classic bisection algorithm to find

. This approach is called water-filling, as it reminds of the process of pouring water into communicating vessels of depth

(being our optimal solution), until the total amount of poured water equals 1 (being our equality constraint). In this analogy, the multiplier

represents the water level.

7. Extending to non-linear constraints

When constraints are non-linear and of the kind and

, the KKT conditions are analogous to the linear case. In (11), it suffices to replace

with

and

with

. This follows the intuition that, in a neighborhood of

, constraints are approximately linear and can be replaced with their first-order Taylor expansion.

References

[1] W. Karush (1939). Minima of Functions of Several Variables with Inequalities as Side Constraints (M.Sc. thesis). Dept. of Mathematics, Univ. of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

[2] Kuhn, H. W.; Tucker, A. W. (1951). Nonlinear programming. Proceedings of 2nd Berkeley Symposium. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 481–492. MR 0047303

[3] Blogpost video version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8KBlVIpA1A&t=1293s

Leave a comment