This post explores the Gauss’s divergence theorem through intuitive and visual reasoning. To engage the reader’s imagination, we use water flux as our running example, although the reasoning applies to any vector field, e.g., electric, magnetic, heat or gravity field. Moreover, to keep things simple we work on the two dimensions, although the same principles extend to higher dimensions.

1. Leaks and sources

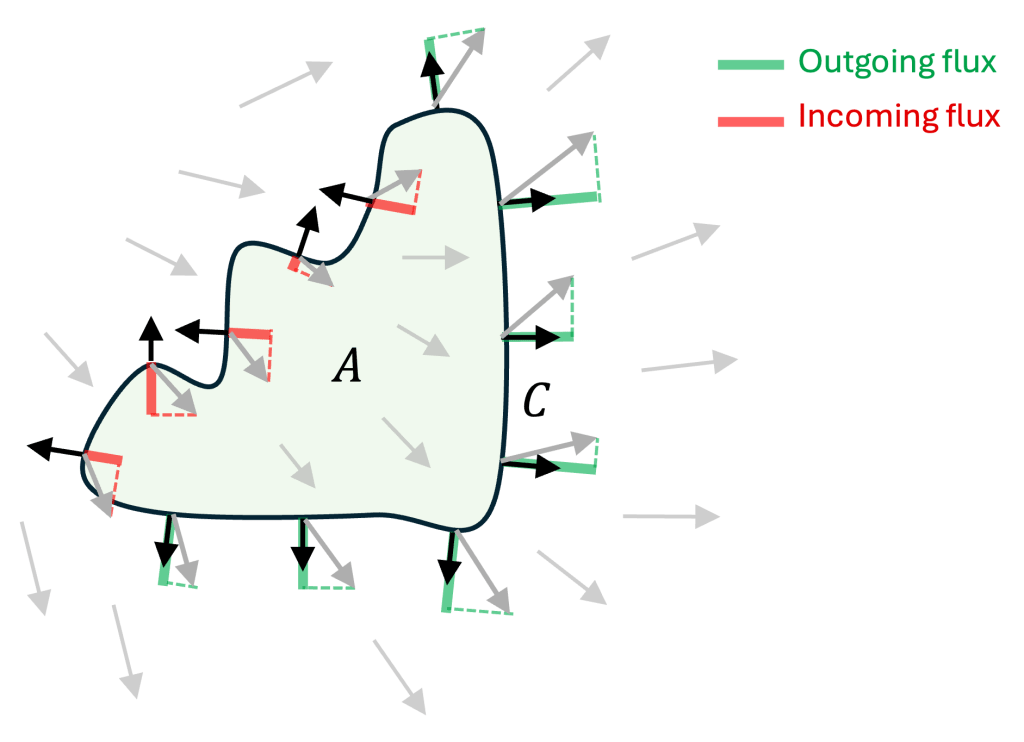

We step into the shoes of a (geeky) plumber aiming to detect a water leak or source within an area and assess its magnitude using integral calculus.

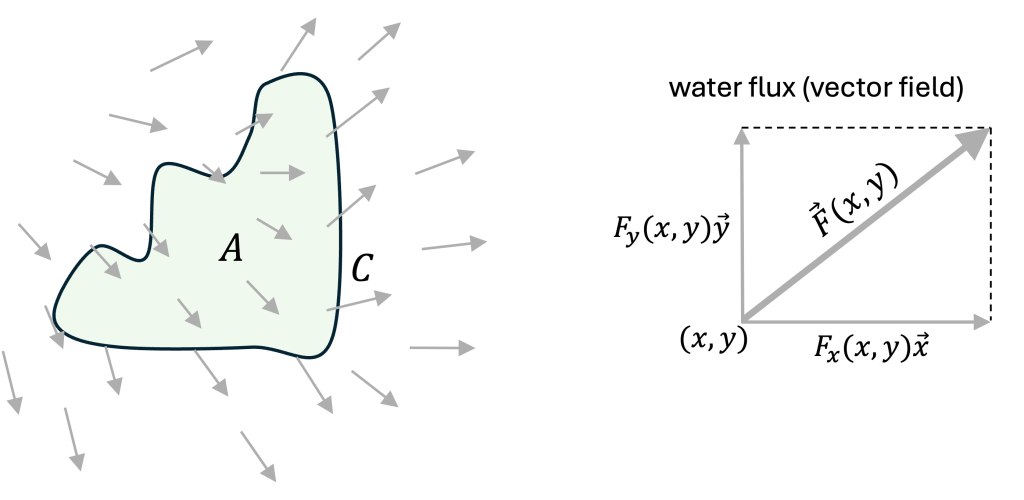

We assume that the (planar) water flux can be measured at any point

:

where is a vector that indicates the flow direction, and its magnitude represents the flux intensity in

.

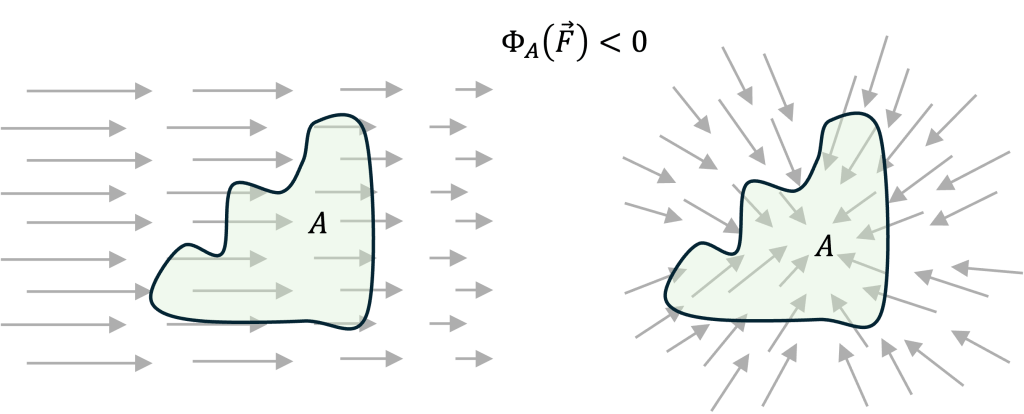

We then compute the net water flux, denoted as , as the outgoing flux minus the incoming flux through

. We conclude that a leak is present within

if

:

If, instead, the net flux is positive, a water source is detected:

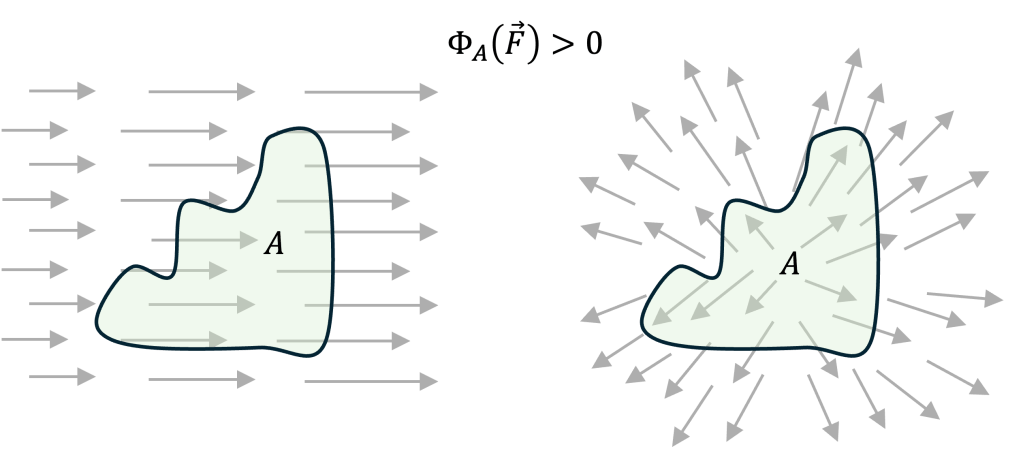

Else, if the flux is null, it means the water stream is conserved after flowing through :

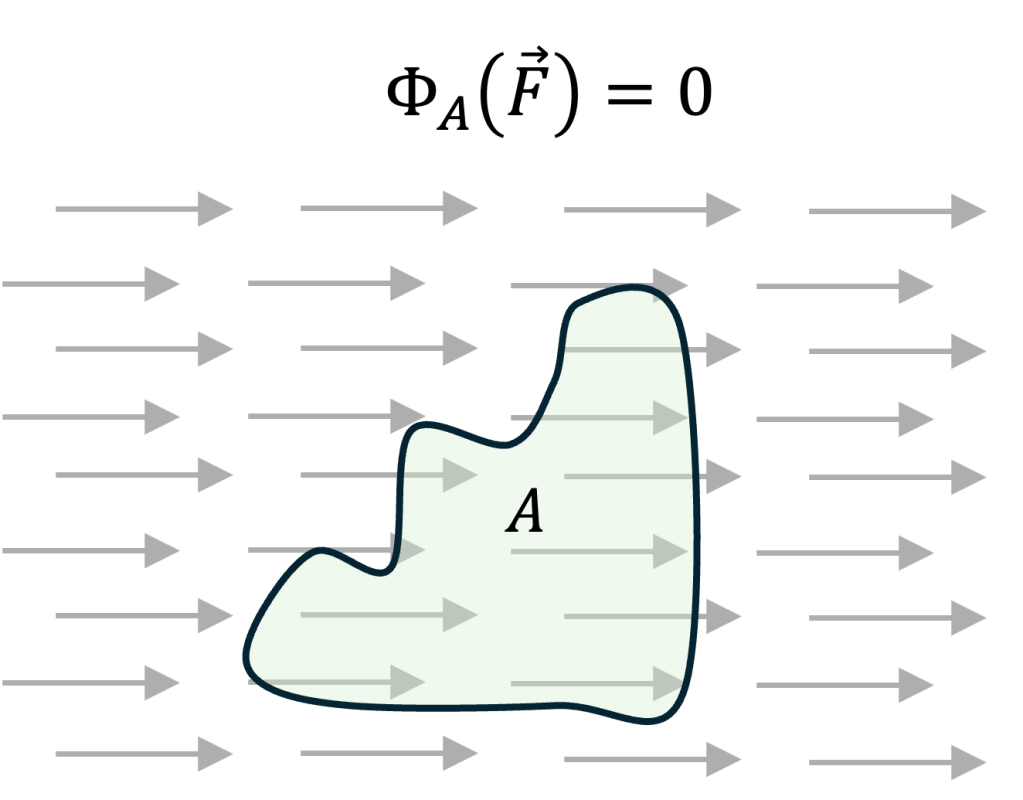

2. Net flux via a line integral

The net flux through

can be computed as follows. Define

as the contour of

. At each point

of

, we evaluate the outgoing local flux in a small neighborhood of length

. This equals the scalar product between

and the outward-pointing unitary vector

perpendicular to

, multiplied by

.

As intuition suggests, if then the local flux is null, while if

and

are anti-aligned then the outgoing flux is negative, i.e., incoming.

Finally, we sum up all local contributions along the contour. More compactly, this can be written as the line integral:

3. Net flux via the Divergence Theorem

The divergence theorem defines an equivalent method to compute the net water flux, as

where is the divergence of

:

Note that the cross-terms and

do not intervene in the definition of divergence.

The divergence theorem is of practical importance because, among other things, the divergence integral is often easier to compute than the line integral since the former only entails scalar quantities.

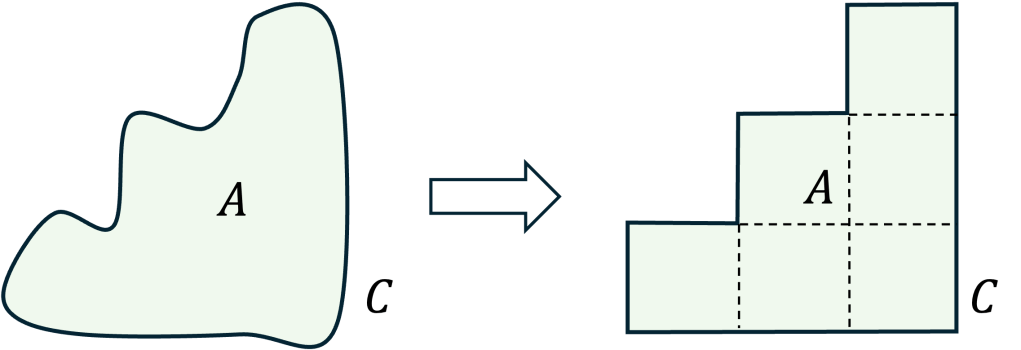

In the following we provide an intuitive justification of (2), organized in four steps.

Step 1. We approximate the area as the collection of a myriad of small rectangles of side

:

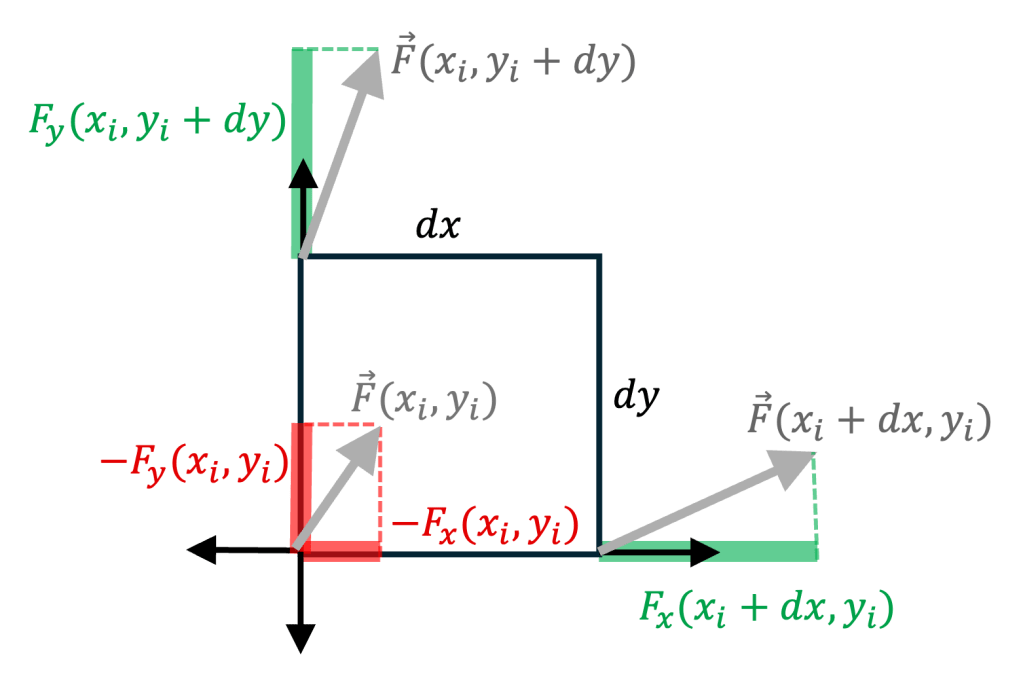

Step 2. We approximate the line integral on the -th rectangle by considering that the vector field remains constant along each (small) edge:

Interestingly, as a by-product, we have just heuristically shown that the divergence is effectively a measure of “net flux per unity of area”, i.e.,

where the area encloses the point

.

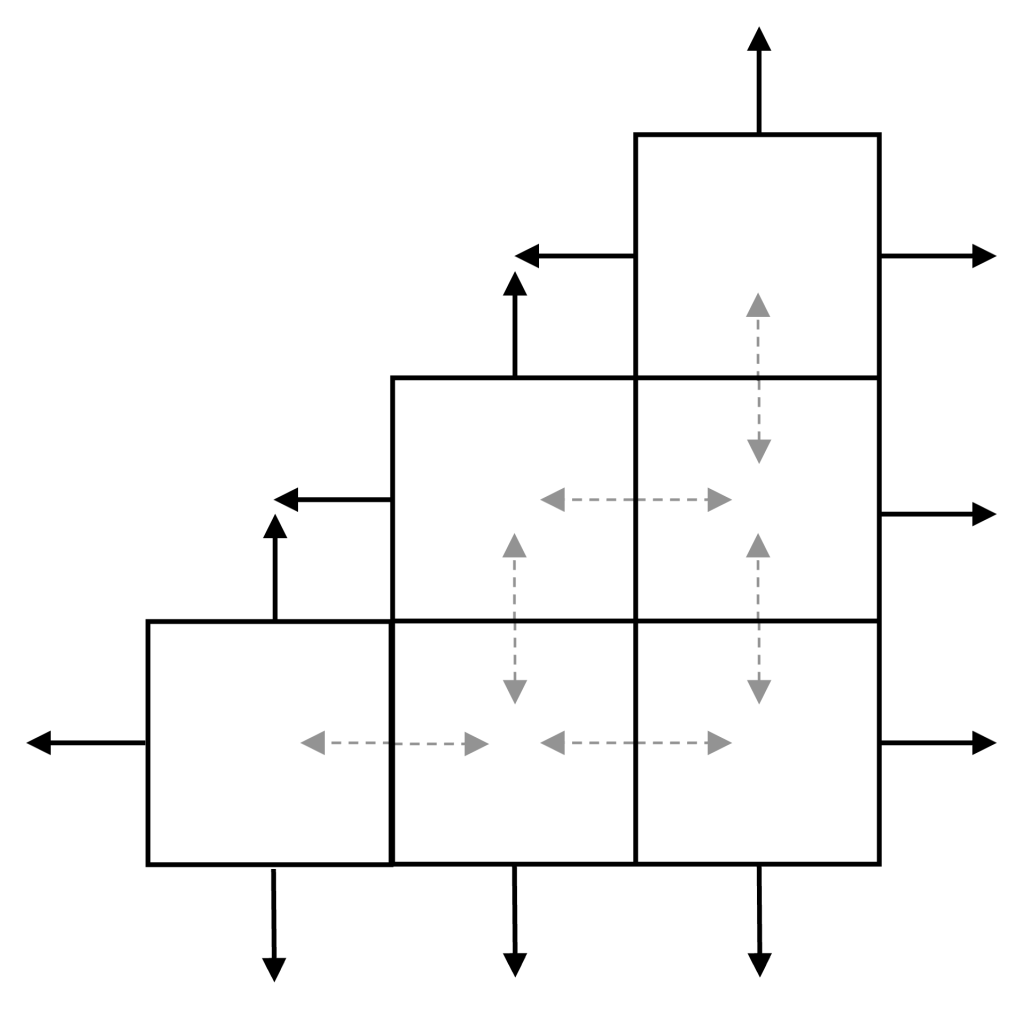

Step 3. When summing the net flux across all rectangles as , an interesting phenomenon occurs. In correspondence of adjacent rectangles, the normals at shared edges are oriented in opposite directions. As a result, the individual contributions of such edges to the line integral cancel each other out, leaving only the contributions from the boundary edges, which—aha!—lie along the contour

.

Therefore, equals the net flux

, which by (7) also (approximately) coincides with the sum of the divergence contributions over the whole area

:

Step 4. By letting the rectangle grid become infinitesimally fine, expression (9) tends to the original claim of the divergence theorem: .

Leave a comment