Chain rule to the rescue!

To train a deep neural network (DNN), one needs to repeatedly compute the gradient of the empirical loss with respect to all the DNN parameters . Since their number

can be huge, it is crucial that the procedure for gradient computation grows “slowly” with

. Back-propagation addresses this successfully by exploiting shrewdly the derivative chain rule, as we discuss in this post.

Supervised learning scenario. In supervised learning, the goal is to predict variable from variable

by training a model on a dataset

containing pairs of realizations

of the aforementioned variables. Classically, the model is defined by a family of functions

parametrized by

. Then, the empirical loss is minimized:

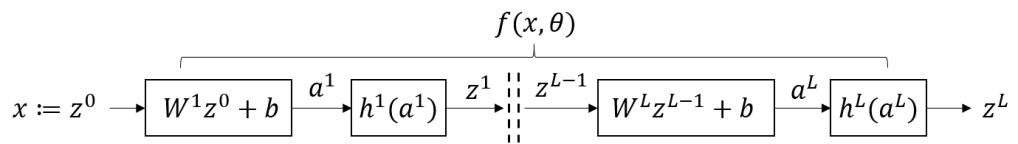

Feed-forward DNN. We here consider that the model takes on the form of a feed-forward DNN, with

fully connected hidden layers where each neuron is connected to all the neurons of the next layer.

We call the (column) vector , which is multiplied by the

weight matrix

and summed to the bias vector

, to finally obtain the vector

. Then, the non-linear (e.g., sigmoid) activation function

, applied individually to each element of

, produces the intermediate variable

. The same procedure is iterated over all

hidden layers as follows:

where for all

. We call

the function resulting from applying equations (2),(3) iteratively over all layers, where

is the collection of all weights and biases. Hence, the DNN output produced by injecting

as input is

.

Gradient of the loss. To minimize the loss via (any variant of) gradient descent, we must compute for each

pair the gradient

.

Finite difference? A (naive) option to compute the gradient is via finite difference:

where is the number of DNN parameters and

is zero everywhere except for its

-th element being 1.

Let us investigate the computation complexity of (5). Evaluating requires to iterate (2) and (3) across all layers, each calling for

and

basic operations (i.e., products, sums and computation of

). To compute the finite difference, such evaluation is then repeated

times. Thus, the total complexity is in the order of

Since the number of parameters can be huge, a complexity quadratic in can be prohibitive. The natural question is: Can we do better? The answer is yes, as we show next.

Preliminaries: Jacobian matrix. Define the function . The Jacobian of

evaluated at

is called

and is defined as:

where denotes the partial derivative of

with respect to its

-th input and evaluated at the point

.

Observe that if is affine, i.e.,

, where matrix

and column vector

, then

.

If is separable across elements of

, i.e.,

for all

‘s, then

is the diagonal matrix

.

Preliminaries: Chain rule for derivative. Define two functions and

and their composition

, such that

for all

. If

and

are both unidimensional (

), then

In the general case, the derivative of the -th component of the composite function

with respect to the

-th input variable

equals the sum over all intermediate functions

of the individual contributions:

More compactly, (8) can be rewritten as the product of the Jacobian’s of the individual functions:

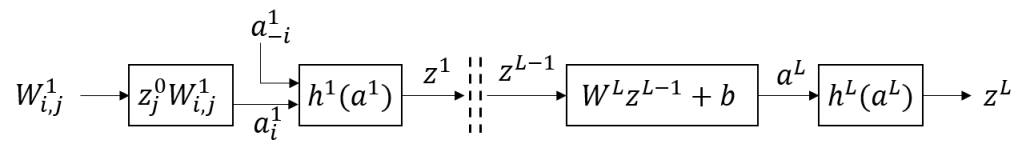

Back-propagation (BP) rule. Our goal is to compute the derivative of the loss function with respect to any weight or any bias coefficient

as efficiently as possible. We start by noticing that if

changes then only

changes at layer

. By chain reaction, this modifies

and, finally, the loss

.

It stems from (2) that the second term is simply . Similarly, the derivative with respect to the bias term writes:

where the second term .

Thus, to compute (10) and (11) we are left with evaluating . By chain rule (9), the vector of partial derivatives

, commonly referred to as the error term, can be computed as:

where each term is calculated as follows:

The key observation is that the error term does not need to be recomputed from scratch at every layer. Rather, one can use an iterative computation with small incremental complexity, in a backward fashion from higher to lower layers.

Back-propagation procedure.

- Forward: Compute the value of all the intermediate variables

given the input

by evaluating (2),(3) at all layers.

- Backward: For

:

- If

, then compute

.

Else, compute incrementally - Compute

- Set

- If

- Return

.

Complexity. As we showed before, evaluating the forward pass requires operations. Remarkably, the backward pass requires the same (order of) number of operations. This leads to an overall complexity being linear in the number of parameters

, in contrast to the finite difference case, characterized by a quadratic complexity.

References.

[1] C. M. Bishop, H. Bishop. Deep Learning: Foundations and Concepts. Springer, 2024.

[2] I. Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, A. Courville. Deep learning. MIT Press, 2016.

[3] S.J. Prince (2023). Understanding Deep Learning. MIT press.

Leave a comment