Gaussian (or normal) variables are all around the place. Their expressive power is certified by the Central Limit Theorem, stating that the mean of independent (and not necessarily Gaussian!) random variables tends to a Gaussian variable. And even when a variable is definitely not Gaussian, it is sometimes convenient to approximate it as one, via Laplace approximation, or to model it as a Gaussian mixture. Gaussian distributions also pop up, e.g., in Bayesian optimization, where an unknown function is modeled as a Gaussian process [1]. And yet, while the uni-variate Gaussian case is simple to grasp (the “bell”!) and the expression of its density function is easy to remember (something like …!), the multi-variate case is often perceived as more obscure and harder to visualize.

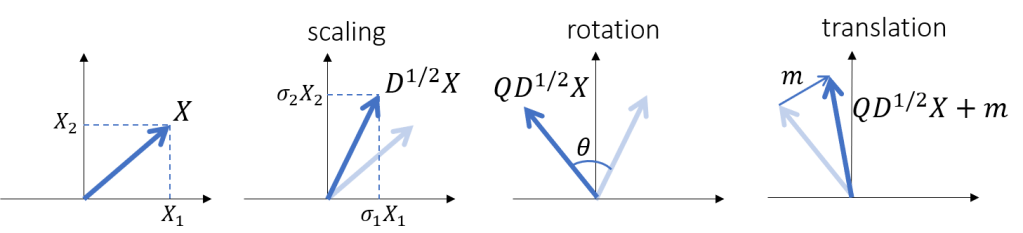

Geometric interpretation. In this post we try to shed some light on multi-variate Gaussian distributions case via a beautiful (and well known) geometric interpretation: any vector of jointly Gaussian variables can be obtained by applying basic geometric operations to a collection of independent standard normal variables (with zeros mean and unit variance), such as 1) scale 2) rotation and 3) translation.

How to read this post. To show that the geometric interpretation holds true we will take no shortcut, and delve first into a couple of preliminary concepts from calculus and linear algebra in Section 1. Yet, the hurried reader can jump directly to Section 2 where we serve the main dish with multi-variate Gaussian variables.

1.1. Change of variables in distributions

Let us first refresh our memory on calculus. Suppose we know the distribution of a certain random variable

. A second variable

is obtained from

via a mapping

.

We want to figure out the relationship between the distribution of

with the original one

. The following is a classic result from, e.g., [2].

Theorem 1 Let

and

be multi-variate random variables with density function

and

, respectively, such that

. Suppose

differentiable and invertible, where

. Then,

Let us inspect expression (1). Its latter term, , is somehow expected: in analogy with discrete variables, the probability that

equals the probability that

takes on the value that is mapped to

via

, namely

. For continuous variables, however, the density is not per se a probability, and the additional term

stems from the chain rule of derivatives. To convince ourselves that (1) holds true, it is useful to derive it in the uni-variate case. We call

and

the cumulative distributions of

and

, respectively. We need to distinguish between two cases, whether

is i) increasing or ii) decreasing. (Note that

is supposed to be invertible, hence there is no option iii)!)

If i) is increasing,

To obtain we compute the derivative of the last expression with respect to

:

Else, if ii) is decreasing,

and

We observe that the two cases i) and ii) can be both written as

since if

is decreasing. We finally notice that (6) is the uni-variate version of the seemingly daunting formula (1) in the multi-variate case!

1.2. Spectral decomposition of symmetric matrices

We now revise another fundamental result, on linear algebra this time: the spectral decomposition of symmetric real matrices, see [3].

Theorem 2 For all

, any symmetric matrix

can be written as the product

, where

is real and unitary (i.e., its rows and columns are all orthogonal:

) and

is a diagonal matrix.

Proof: We split the proof in three parts: 1) has real eigenvalues, 2)

has real eigenvectors, 3) the eigenvectors of

are orthonormal.

Part 1: has real eigenvalues. If

is an eigenvalue of

, then there exists a (eigen-)vector

such that

, which can be rewritten as

, where

denotes the Hermitian transpose. Its conjugate can be expressed as:

where we exploited the property for any matrices

and the fact that

since real symmetric.

Part 2:Each eigenvalue of

has a real eigenvector. Suppose that

is a complex eigenvector associated to

, namely

. Since

are real, then we can dissociate the expression into its real part

and imaginary part

. Then,

and

are both real eigenvectors with eigenvalue

. We have then proved that there exists a matrix

stacking the real eigenvectors of

on its columns and a diagonal matrix

collecting eigenvalues on the main diagonal such that

. We still need to prove that

is unitary. Since

, we can also conclude that

which will prove the thesis.

Part 3. is unitary. We prove it by induction. Clearly, it holds for

. Then, suppose that it holds for matrices

of dimension

(then,

). Now, let

be of dimension

. Call

one of its real eigenvectors, normalized such that

, with associated eigenvalue

. Then, we find

column vectors

orthogonal with each other and also orthogonal with each other:

To construct the matrix that diagonalizes

we first build in the following way. Since

is symmetric,

is also symmetric (in fact,

). Then, by induction hypothesis, it can be decomposed as:

Lastly, we define as

. Observe first that

is unitary, from (8). Then, compute:

Let us first inspect the diagonal blocks. Since is a unitary eigenvector of

, then

. From (9) it stems that

. We now turn to the off-diagonal blocks, which are the same up to a transpose. Since

is an eigenvector of

, then

via (8). Therefore, we conclude that

which proves the thesis for matrices of dimensions

, and the theorem by induction process.

1.3. Eigenvalues of positive semi-definite matrices

This third and last part of our warm-up section refines the result above for positive semi-definite matrices. A (real) matrix is positive semi-definite if

for all (real) vectors

. Prominent examples are covariance matrices. In fact, consider any random vector

and its covariance matrix

. Then, we realize that

We next show that, if the symmetric matrix in Theorem 2 is positive semi-definite, then the diagonal matrix

has non-negative values on its main diagonal, see [3]. This result will serve us well in Section 2 where

carries variances on its diagonal, which clearly cannot be negative.

Theorem 3 The eigenvalues of a symmetric positive semi-definite matrix are all non-negative.

Proof: We compute for a semi-definite matrix

. It stems from Theorem 2 that we can write

, where

is the

-th column of

. Since

are

independent vectors (in fact,

is invertible!), they form a basis of

. Therefore,

itself can be written as a linear combination of vector

‘s, i.e.,

. Hence,

By the orthogonality property of ‘s (

for

,

for all

),

By hypothesis, . Since this must hold for all

(hence, for all

), then

for all

, which proves the thesis.

2. The main dish: Gaussian variables

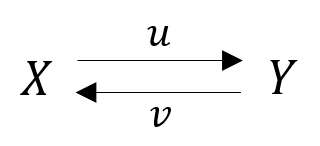

After such a warm-up, we can address the main topic of this post: multi-variate Gaussian variables. Next we show the two-way relationship between independent and correlated Gaussian variables:

- independent

correlated: by scaling, rotating and translating independent standard (i.e., with zero mean and unit variance) Gaussian variables we still obtain Gaussian variables, correlated with each other (Section 2.1)

- correlated

independent: any vector of correlated Gaussian variables can be interpreted as the result of appropriate scale, rotation and translation operations applied to independent standard Gaussian variables (Section 2.2).

2.1. From independent standard to correlated Gaussian variables

Consider a list of

independent standard Gaussian variables (i.e., with zero mean and unit variance). Recall the (marginal) probability density function (pdf) of each individual

:

Since all variables are independent, the multi-variate pdf of the whole vector is simply the product of the individual pdfs:

To spice things up, let us transform into a more expressive random vector

, via basic operations such as:

- scale, obtained by multiplying each

by a positive scalar

(this is without loss of generality:

and

have the same distribution!). In matricial form, the result of scale is

, where

is a diagonal matrix carrying

‘s over the main diagonal (note that the exponent

will come in handy in the following);

- rotation, resulting from multiplying the scaled vector

by a rotation, or unitary, matrix

, such that

. In two dimensions (

),

We will see that these first two operations introduce correlation across different elements of the random vector;

- translation, by simply adding a constant offset

to the scaled and rotated vector

.

The resulting random vector writes:

To compute the pdf of we can apply Theorem 1 on change of variables. But before, we still need to:

- compute the inverse function

, mapping

to

. Fortunately, this is easy algebra:

- compute the determinant of the Jacobian

. By exploiting the property

we deduce that:

where the last expression stems from(in fact,

, hence

).

We can finally exploit Theorem 1 to transform the pdf of the independent standard variables , in Equation (17), into the pdf of the transformed variable

:

We reached our goal but we are quite not satisfied yet: the last formula does not look like what we usually find in textbooks, e.g., [1]. Let us then conveniently define the matrix as:

After realizing that , we finally get to the classic expression of multi-variate Gaussian variables:

The vector and the matrix

carry two key pieces of information on

, namely its mean vector and covariance matrix, respectively. In fact,

since and

.

2.2. From correlated to independent standard Gaussian variables

In this last section we take the reverse path and, given a vector of Gaussian variables with mean

and covariance matrix

, we want to retrieve (if any!) the basic operations (scaling, rotation and translation) that led from independent normal variables

to the correlated

. To this aim, all ingredients are there: it suffices to invoke Theorem 2 and decompose

as

, where as usual

is a unitary matrix and

is diagonal. Then, Theorem 3 informs us that

carries non-negative number on its diagonals, hence

is well defined and real. Thus, previous Section 2 tells us that

can be interpreted as the scaling by

, rotation by

and translation by

of a set of independent normal Gaussian variables

.

Take-home message: Suppose you are given a set of Gaussian variables with a certain covariance matrix

and mean

. To gain precious geometric intuitions, decompose

to retrieve the scale (via

) and rotation (via

) operations that connect

with a simple vector of independent standard variables!

References

[1] Bishop, C. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning. Springer.

[2] Billingsley, P. (2017). Probability and measure. John Wiley & Sons.

[3] Strang, G. (2022). Introduction to linear algebra. Wellesley-Cambridge Press.

Leave a comment